How to personal finance (DRAFT)

Hi, I’m Lorenzo from Italy 🇮🇹. Like many young people here, I grew up in an environment where talking about money 💶 was often considered taboo. But as with many outdated traditions, such as the patriarchy, I’ve chosen to break the cycle. I’m determined to demystify money, learn about it, and understand how it influences our lives without letting it become a shadow over our souls 👻.

DISCLAIMER: I am not an expert, nor do I claim to be. This text is a personal interpretation of what I have learned. Throughout the text, you will find references supporting any statements and claims. Any personal interpretations will be clearly labelled as “personal thoughts”

Basic rules of personal finance

As you might expect, there are no “official” rules, as everyone’s needs, goals, financial situation, and mindset are unique.

The personal finance is based on a three rules scheme:

- Track and reduce your spending 💸📉

- Improve your income 💼📈

- Invest accordingly your objectives 📊🎯

Track and reduce your spending

The first and most essential step in personal finance is to track the cash flowing out of your pockets. While this may seem simple or even trivial, it is anything but. Understanding where your money goes is vital for identifying needs and recognizing areas where you can cut back. It’s important to note that tracking expenses isn’t about reducing your lifestyle; it’s about gathering data to assess your financial balance. With this information at hand, you can thoughtfully set goals and create a strategic plan to achieve them.

Once you’ve tracked your expenses and made cuts where you can or want to, you’ll have a clear picture of your average monthly spending. If you receive a regular salary, you can then calculate your monthly net surplus by subtracting your total expenses from your income. This surplus represents the extra cash available each month that enriches your bank account…. and now?

The four pillars of your net worth

Add introduction

Net worth

An individual’s net worth is determined by subtracting total liabilities from total assets. Liabilities encompass various types of debt, such as mortgages, credit card balances, student loans, and car loans. Additionally, liabilities include financial obligations like unpaid bills and taxes that need to be settled. An individual’s assets can include balances in checking and savings accounts, the value of securities such as stocks and bonds, real estate holdings, and the market value of vehicles. Net worth is the amount remaining after all assets are liquidated and personal debts are fully paid off.

This might be confusing, let’s give some quantitative examples:

For example, consider a student who has no debts and holds €5,000 in a bank account. Additionally, there is a €2,000 fund set up by their family in their name. In this case, the student’s total assets amount to €7,000 (€5,000 in the bank account + €2,000 in a separate fund). Since it has no liabilities, its net worth is €7,000.

Alternatively, consider a 40-year-old individual who owns an inherited house valued at €250,000 and has €10,000 in a bank account. However, it has a car loan debt of €20,000. Its total assets amount to €260,000, which includes the value of the house and the bank account balance. The total liabilities consist of the €20,000 car loan. Its net worth is calculated as €260,000 in assets minus €20,000 in liabilities, resulting in a net worth of €240,000.

Simple, isn’t it? No worries in a few lines it is going to become a nightmare

Net worth managing

Now that we can calculate our net worth and understand our expenses, it’s natural to ask: How much money should I keep in my bank account? Should I invest the rest? If so, where and how? These are complex questions without straightforward answers. The most accurate response is, depends. Fortunately, this guide is meant to provoke thought on these topics rather than provide a one-size-fits-all solution. The best part is that you can develop a strategy tailored to your unique circumstances.

To simplify the management of our net worth, we will explore a four-pillar framework. This scheme is inspired by the model presented by Prof. Paolo Coletti in his Personal Finance course available on YouTube (“Educati e Finanziati”), which is offered exclusively in Italian.

- 1st pillar: Cash/Liquidity – This represents the funds needed to cover daily expenses and maintain financial stability for routine needs.

- 2nd pillar: Emergency found – This is a reserve of easily accessible cash set aside for unexpected, significant expenses. It serves as a safety net, allowing you to manage unforeseen financial challenges without disrupting your daily budget or needing to dip into your invested funds.

- 3rd pillar: Planned expenses – This involves saving and/or safeguarding money for specific future goals or planned expenditures. It ensures that funds are allocated for predetermined purposes, such as a major purchase, vacation, or upcoming life event.

- 4th pillar: Invest – This refers to money you don’t need right now and won’t need for at least 10 years. The goal is to build wealth and generate returns for long-term financial objectives, such as retirement.

1st pillar (Cash)

This is a crucial part of the framework that supports your financial well-being. Each pillar serves a distinct purpose and comes with its own set of guidelines to help you manage your finances effectively.

OBJECTIVES

- Cover daily expenses accommodating for possible small order volatilities (e.g. bills, small trips, etc.)

- Minimize the amount of money that is not needed (and make something out of it)

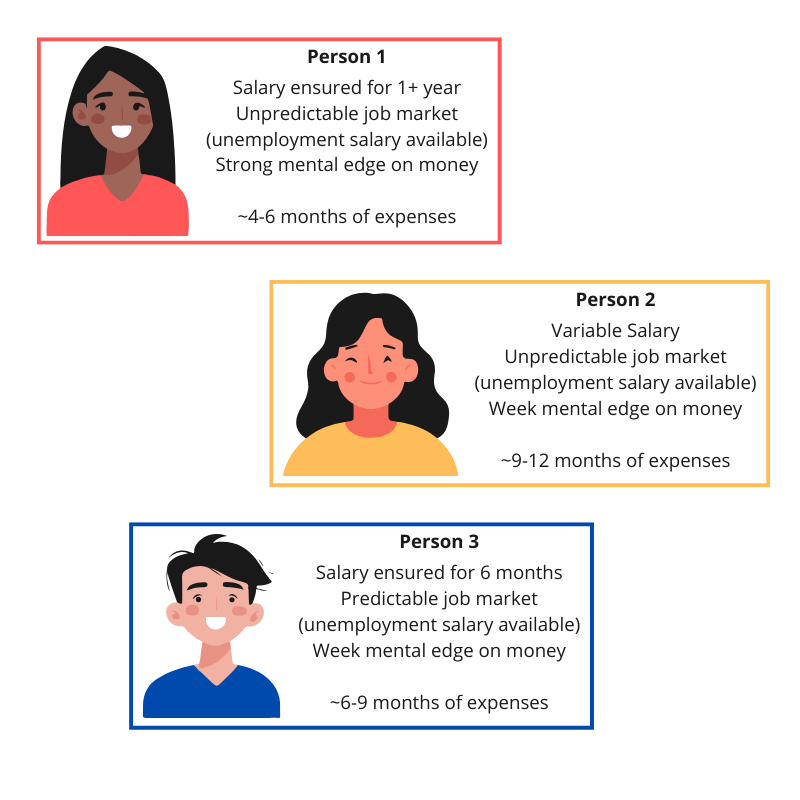

The big question is now… How many euros should I keep in my bank account? Again, it depends! But there is a simple rule. Tracking your expenses provides a clear understanding of your monthly living costs. To maintain financial security, it’s advisable to keep a reserve in your account equivalent to a multiple of your monthly expenses. This multiple typically ranges from 3 to 12 months’ worth of living costs, depending on your personal circumstances and financial goals.

Below are some examples based on typical individual profiles:

See? It really depends. My suggestion is to find what works best for you. This approach will give you peace of mind and help you avoid unnecessary stress about money. If seeing a low balance in your bank account causes stress, consider adjusting this factor. It has only a minor impact on the overall effectiveness of the strategy but can significantly ease financial anxiety.

So imagine that you spend 600€ per month and you are a “PERSON 1” type. For you then is not necessary to keep more than ~3000€ in your bank account.

Now, what to do with the rest? That’s the role of the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th pillar.

2nd pillar (Emergency)

Let’s say you’re confident in the “limit” set for your first financial pillar and decide to invest everything beyond that—stop right there! What if an unexpected expense of €2,000 or more arises? This could deplete your first pillar entirely and erode your financial safety margin.

Your instinct might be to liquidate investments from your third and fourth pillars to cover the cost. However, this approach is inefficient and could lead to financial losses (the reasons for this will be explained later).

To fully understand the role of each investment product and determine which ones are most suitable for the remaining pillars, it is essential to delve into the concept of risk in financial investments.

The digression of risk-return trade-off

To fully understand this we first need to introduce two important quantities: volatility and risk. (Deep dive on it)

The volatility of an asset refers to the degree of variation in the price of an asset or portfolio over time. It is a statistical measure that indicates the extent of fluctuations in the value of an investment. High volatility means the investment’s price can change dramatically over a short period in either direction, while low volatility indicates that the price changes at a steadier and more predictable rate. Volatility is commonly measured using standard deviation or variance, and it is often used to assess the risk level associated with an investment.

Risk in the context of investments refers to the potential for losing some or all of the original investment or the uncertainty regarding the expected returns. It represents the possibility that an investment’s actual outcome may differ from the expected outcome, including not only financial loss but also underperformance relative to expectations.

High volatility and risk are often linked, as investments with greater price fluctuations tend to be perceived as riskier. However, this direct correlation primarily holds for short-term periods, such as days, weeks, or perhaps a few years. When examining longer periods of time, the relationship between volatility and risk becomes more complex, requiring the inclusion of a third variable: the timeframe of the investment.

To illustrate this, consider the following example: Suppose an investor is evaluating two assets: Asset A, known for its high daily volatility, and Asset B, which shows steady, low volatility. Over the course of a few weeks, Asset A’s price might swing wildly, presenting substantial risk to an investor focused on short-term gains. Conversely, Asset B’s stable price provides a safer choice for short-term investors.

However, when the investment horizon extends to several years, the picture can change. Asset A, despite its daily fluctuations, may show an upward long-term trend, potentially yielding higher returns. Asset B, with its consistent performance, might not provide as much growth over the long term. Here, volatility’s impact on perceived risk diminishes, as the investor’s focus shifts from short-term fluctuations to long-term growth patterns. This relationship shows that volatility alone cannot fully define risk without considering the timeframe. Short-term investors may indeed face higher risk with volatile assets, but long-term investors might accept such volatility as part of a strategy for higher potential gains, effectively managing risk through diversification and time-based mitigation.

A quantitative explame…

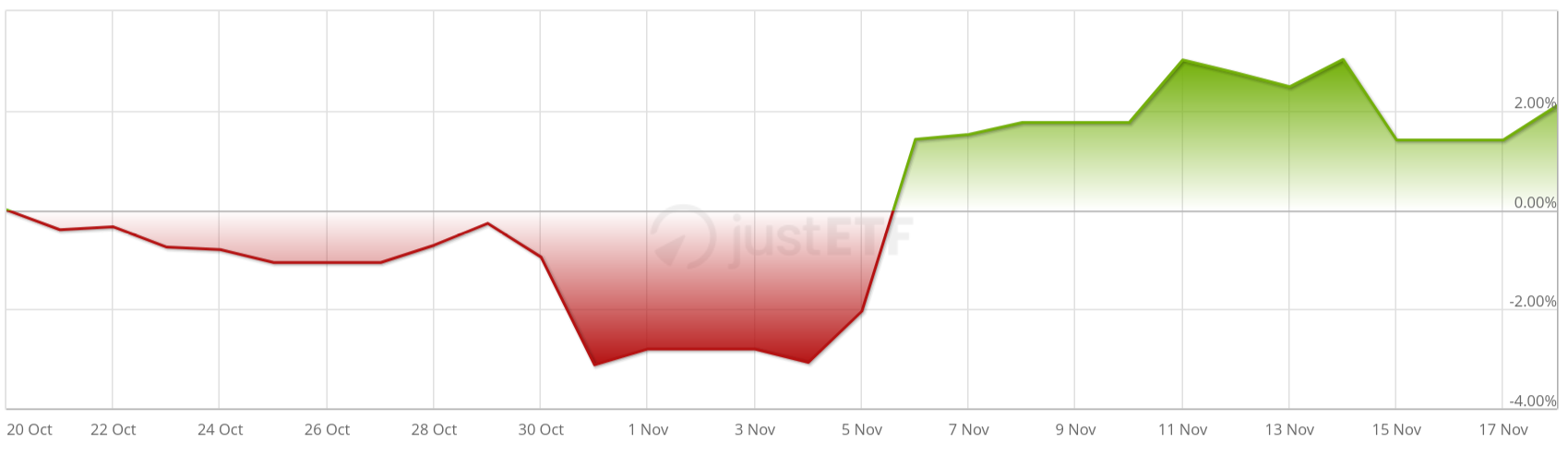

Imagine purchasing 1 stock on October 20, 2024. Below is an example graph showing the percentage variation of the stock’s value over time.

As shown, the stock value fluctuates between -3% and +2% within just one month—a relatively mild swing compared to extreme events like the COVID-19 market crash, where stocks lost around 20% in a single week. In this case, the short-term risk is high; if you bought the stock on October 20, 2024, and sold it on November 1, 2024, you would incur a loss due to the price drop within that brief period.

However, consider a different scenario: you purchase the stock on January 1, 2018, and hold it until November 19, 2024.

The monthly oscillations are still present over the long term, but in this 7-year example, there is an overall growth of approximately 125%. This means that if you had invested €100 at the start, you could sell it for around €225 by November 19, 2024. It’s important to note that this is a simplified example to illustrate the concept; actual investment performance varies and depends on numerous factors.

The key takeaway is that volatility is not synonymous with risk, especially when viewed over extended periods. While short-term fluctuations can be nerve-wracking for investors and indicate higher risk, holding investments for longer timeframes (generally 10 years or more) often mitigates this risk. Over such periods, market volatility tends to smooth out, and investors may benefit from the long-term growth trend of the stock market. (you may ask why should it grow? At the beginning of the 4th pillar section we will see why is not that far from reality)

Other types of investments, such as bonds or savings accounts, have lower potential gains but also exhibit smaller volatility. These investments reach what can be considered the “risk-free” zone more quickly, providing steady, predictable returns suitable for risk-averse investors.

This example underscores the importance of aligning investment strategies with one’s timeframe and risk tolerance. While stocks can be volatile in the short term, longer holding periods typically reduce the associated risk, making them a viable option for those with long-term financial goals.

Deposit Funds (Emergency):

- Volatility: Lowest volatility. Moreover, they are typically insured by financial institutions.

- Return: Lowest returns, often a few points above the inflation rate.

- Suitability: Best for short-term savings or emergency funds.

Bonds (3rd and 4th pillars):

- Volatility: Moderate; safer than stocks but can be affected by interest rate fluctuations.

- Return: Higher than deposit funds; provides predictable income through interest payments. Depends on the bond interest set by EU (for EU bonds ofc)

- Types: Includes government and high-grade corporate bonds, which are generally more stable.

Stocks (4th pillar):

- Volatility: Highest volatility and economic influences.

- Return: Highest potential returns through dividends and capital appreciation.

- Suitability: Ideal for long-term investments and those with higher risk tolerance.

How to build an emergency fund

To build your emergency fund, you first need to determine its size. This decision, like others in personal finance, depends heavily on your individual needs. While emergencies are, by definition, unexpected, many are still somewhat predictable. For instance, if you don’t own a car, or property, have children, pets, or any other significant responsibility that could incur a large, unexpected expense, you might not need a very large emergency fund.

Let’s look at a practical example: suppose you work with your PC. If your PC were to break, it would directly impact your ability to earn an income. In this case, your emergency fund should include enough money to replace your PC. You might also want to account for potential damage to other essential devices, like your smartphone. Additionally, if you know you’ll be renting for the foreseeable future, your emergency fund could cover a deposit in case you need to move unexpectedly.

For this scenario, an emergency fund of around 4-5k could suffice—enough to cover these specific needs without going overboard.

It’s also important to note that you don’t always need to move money from your emergency fund immediately. If you have time to prepare (e.g., you’re planning to move homes in a few months), you can temporarily adjust your liquidity threshold (1st financial pillar) and then reallocate funds once you’ve settled into a new equilibrium.

As you can see, mastering personal finance isn’t about rigidly following a rule (often created by someone else) but about developing the ability to adapt your strategy as your life evolves. Flexibility and foresight are key to navigating your financial journey effectively.

How/Where to invest it?

Every time that you want to take a decision in personal finance it is important to fully address the aim of that move and therefore its needs. Let’s go through this workflow together:

We decided that our emergency fund is ~10k euros. What are our needs? They should be instantly available, but since they are a good amount we do not want to keep them liquid (inflation will constantly eat them up). We want to defend them from inflation, so we can invest them in tools with expected values equal (or lucky superior) to inflation.

Since specific tools and methods strongly depend on the period I will include specific indications of possible tools in a separate post, that I will update periodically.

3rd pillar (Planned expenses)

The third pillar of your financial plan is designed to cover foreseeable expenses that will arise in the short- to mid-term, typically within the next five years. These are not emergencies, nor are they part of your day-to-day spending, but rather planned financial commitments—such as a car purchase, home renovations, or an upcoming wedding. Since you already know these expenses will happen, the goal is to preserve your capital with a small return.

To achieve this, the best approach is to invest in fixed-income instruments, such as government bonds. These assets provide stability, as they are less volatile than stocks and offer “almost” guaranteed capital if held to maturity. Unlike cash, which loses value due to inflation, fixed-income investments help maintain your purchasing power while keeping your money relatively accessible when needed.

Let’s take an example: Suppose you plan to buy a car in three years and estimate the cost to be €20,000. Instead of keeping this amount in a low-interest savings account, you could invest in a government bond with a three-year maturity that offers a 3% annual return. By the end of the term, your investment would grow to approximately €21,800—covering both the expected cost and a small buffer for inflation.

By structuring your previsional expenses in this way, you ensure that your money is protected against inflation rather than sitting idle or losing value over time.

4th pillar (Long term goals)

The fourth pillar is dedicated to long-term investments. However, before even considering this pillar, you must first secure the previous three—ensuring you have cash for daily needs, an emergency fund, and provisions for foreseeable expenses. Only once these foundations are in place is resonable to allocate funds toward long-term growth. If we’ve designed the first three pillars well, the money allocated here is simply excess capital—funds you simply do not need.

Okkkkkk, but now you might ask… what are stocks? In simple terms, a stock represents ownership in a company. When you buy a stock, you are purchasing a small fraction of that business, making you a shareholder. If the company grows and becomes more valuable, so does your share. Stocks generate returns in two ways: price appreciation (the stock’s value increases over time) and dividends (some companies distribute a portion of their profits to shareholders).

As we already said, this pillar is designed for financial goals that are at least 10 years away—but ideally even longer. Unlike short- to mid-term investments, where capital preservation is key, here the focus shifts toward growth. The perfect asset to fullfill this objective are stocks since, in such long investment windows, they tend to outperform other asset classes, making them the best tool for building wealth for you retirment. Investing in stocks comes with volatility, but time is your greatest ally. Historical data shows that despite short-term fluctuations, markets tend to rise over decades. This means that as long as you don’t need to withdraw funds prematurely, you can ride out downturns and benefit from long-term appreciation. I will provide you a proof of this in a future post… stay tuned!

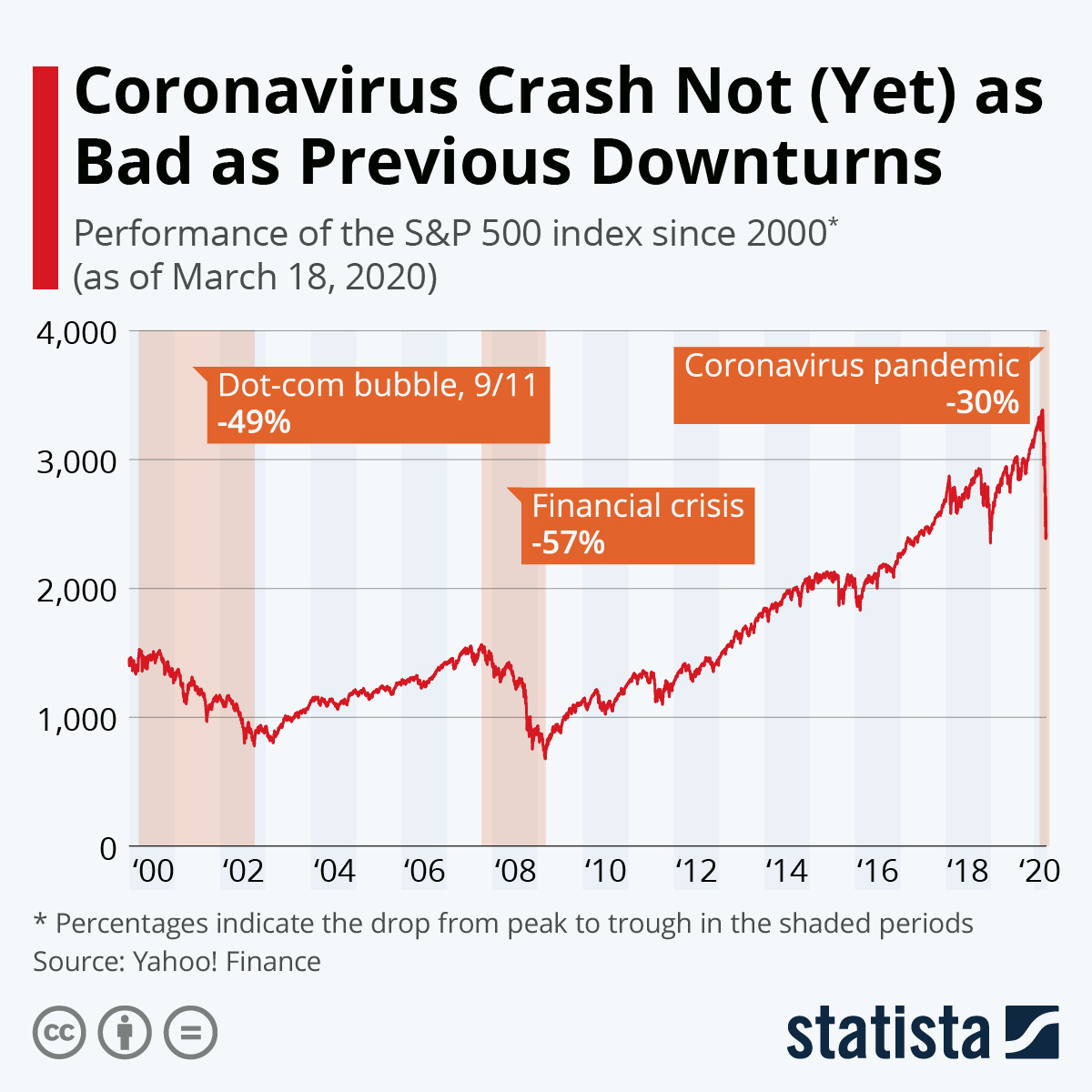

Big Disclaimer: Stock Market Volatility is Real! Before diving into stocks, it’s crucial to understand just how volatile they can be. Unlike cash or bonds, stock prices fluctuate constantly, sometimes experiencing extreme downturns. A well-diversified portfolio may still face drawdowns of 30%, 40%, or even 60% during severe market crashes. These drops are not theoretical—they have happened multiple times throughout history and will happen again.

This is why investing in stocks requires the right mindset. If you panic and sell during a downturn, you lock in your losses. Instead, you must be mentally prepared to stay invested and stick to your strategy even when the market is deep in the red. Volatility is not risk—risk is selling at the worst possible time. Time is your greatest asset, and the longer you stay in the market, the more likely you are to see strong positive returns.

If the idea of seeing your portfolio temporarily lose half its value makes you uneasy, that’s a sign that you may need to adjust your asset allocation or revisit your financial plan. Successful investing is not just about picking good stocks—it’s about having the emotional resilience to hold on when things look bad. Patience and discipline are what separate successful investors from those who panic and lose money. In the next post I will try to prove you that stock market is not that risky as you may think, even if is good to recall that is practicaly impossible to perfermor a risk-free investment (but you can get close to it).

See this article on statista.com which highlight the three recent big drwdown of the stock market.